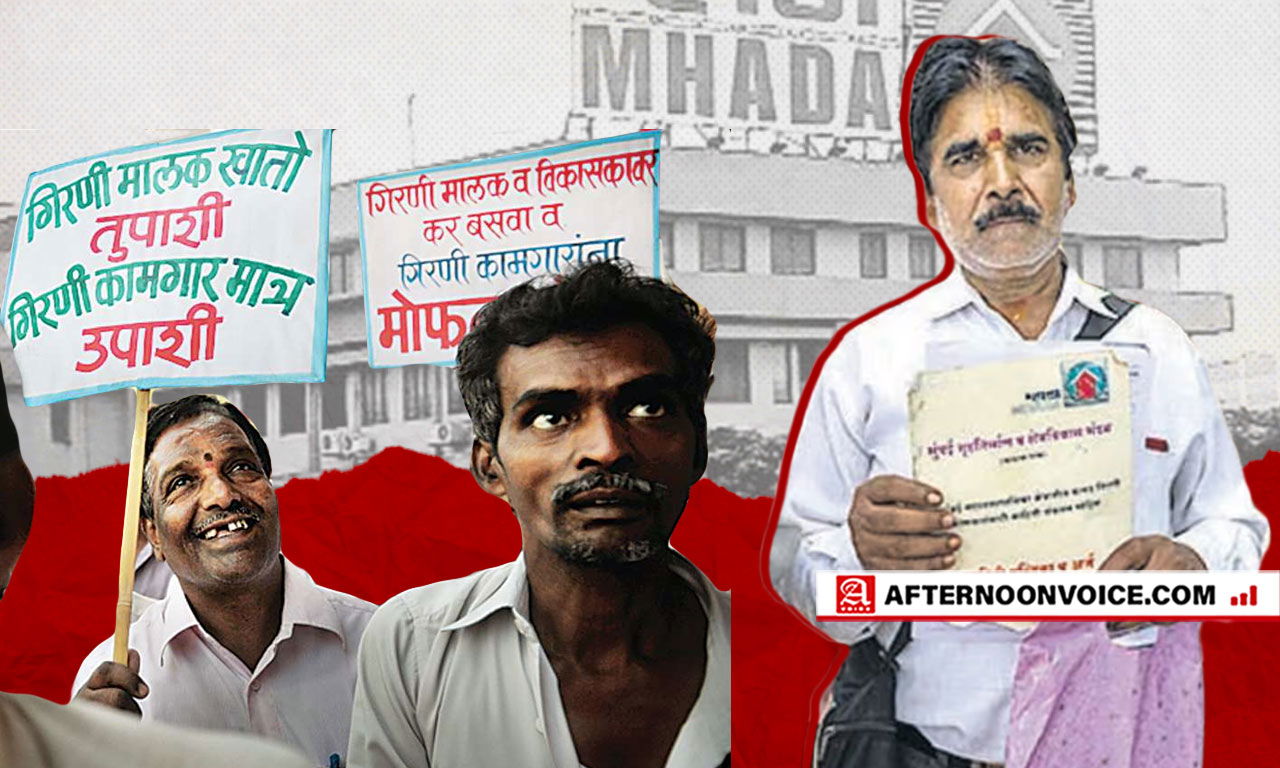

Millworkers misery is not new to the city; once mills and mill workers were the pride of Mumbai. But gradually, many mills got shut down, and generation after generation, the mill workers’ families still struggled for justice. In the recent past, thousands of former mill workers in Mumbai are still waiting for the houses they were promised in 2016. Delays in paperwork, changes in government, and the use of these ready homes as quarantine centers due to COVID-19 have all contributed to the postponement. The houses, which were supposed to be handed over on Dussehra, are now expected to be completed by November. However, many workers are unsure and worried about the extended wait and the worsened condition of the houses.

In 2016, the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority (MHADA) held a lottery for subsidized housing for former mill workers and their families. Each was promised two flats of one-room kitchen measuring 160 square feet in Kongaon, Panvel, for Rs 6 lakh. The land belonged to the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA), where the agency built the houses. Many paid up in 2019 after dipping into their savings or taking out loans. Many of them sold their assets and are now literally bankrupt. The ready homes were repurposed by the Panvel Municipal Corporation as quarantine centers for affected patients. Post-pandemic, the buildings were left in awful condition, with broken doors and sinks stolen. The houses could be handed over in such a state. The conditions of these new houses have deteriorated. MHADA then floated a tender for repairs, adding an expense of over Rs 52 crore. The government literally ignored the urgent requirements of the people.

The mills of Mumbai have an interesting history; when the British and Portuguese decided to begin trade in India, they decided to make Mumbai their foundation. It began around the late 1840s, when mills began to plant themselves around a location that is now the central part of Mumbai. The mills were set up towards central and south Mumbai when the islands still existed and the land had not been reclaimed. A significant rise in port activity led businessmen, mostly from the Parsi community, to invest in the rising trade in Mumbai. Mills were then built with large hall spaces in order to function with at least one thousand workers in them.

The first mill in Bombay was projected in 1851 by C Nanabhai Davar and commenced work in 1854 under the name of Bombay Spinning and Weaving Company. The initial mills began around Tardeo and Byculla and later began moving northward. The mills were once located in the central part of Bombay, in a vast area known as Girangaon—the village of the mills—that encompasses the localities of Byculla, Chinchpokly, Lalbaug, Poybawadi, Parel, Lower Parel, Worli, Deleslie Road, and Jacob Circle to Dadar. The walls of these once-gargantuan structures remain in despair today in the company of junkies, and perhaps we occasionally witness couples whose stories fade away with time. Ironically, the Shiv Sena earned its spurs as a party when it took up the cause of mill workers in the 1960s. Today, Shiv Sena unions have lost most of their ground in the area as they failed to protect the workers’ interests. In the recent past, Shiv Sena has also lost its existence as it used to.

The first textile mill, Bombay Spinning Mill, was set up in 1854 in response to Britain’s need for cotton textiles. At that time, cotton was imported from the United States but when the Civil War broke out in that country, supplies stopped. This enabled the Indian textile industry to flourish. In 1961, the mills employed more than 2.5 lakh people. But a decline in imports owing to stiff competition from other countries started to lead the mills to ruin. By the 1980s, the majority of the mills had closed after a prolonged strike. Gradually, there were 58 mills, employing a mere 20,000 people. Of these, 32 are privately owned, 25 are owned by the NTC and one is owned by the state government. Twenty-nine private mills, declared sick by the Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR), have shut down. The few mills operated by the NTC have incurred massive losses.

The Mills issue has remained mired in controversy for years. For instance, activists say many private mills do not have the right to sell their property as they were given the land on lease for industrial purposes. Then there is the issue of compensation for workers. Over the years, several plans to restructure and make optimum use of the mill area were proposed. They remain on paper. Now that the mill lands have vanished, a whole chapter of Mumbai’s history is lost. But a government keen on redevelopment does not want a millstone around its neck in the form of the obligation to preserve the past.

The strike led by Dr Datta Samant involved 247,189 Mumbai mill workers and brought the city to a standstill. The 1982–83 strike was the last industrial action by the Mumbai mill workers when the city witnessed an industry-wide strike, bringing the workforce to the center of politics. While the present-day public memory of the strike has receded, it is important to remember the event that fundamentally transformed the city of Mumbai.

The conflict between the mill workers and the owners began over the issue of bonuses. However, as the conflict gained momentum, other demands were added, such as providing for an ad hoc increase in the wage per month from Rs 120 to Rs 195 per month, depending on the years of service. Secondly, to make the badly (make a shift) workers permanent who had worked for an aggregate period of 240 days. Thirdly, payment of House Rent Allowance (Rs 52 per month), Leave Travel Allowance (Rs 42 per month), and Educational Allowance (Rs 30 per month). Substantial improvement in leave facilities such as privilege leave, casual leave, sick leave, and paid holidays was also one of the demands.

Finally, the strikers demanded non-recognition of Rashtriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh (RMMS) as the representative union and the sole bargaining agent for workers. These demands shocked the employers. The mill owners were able to put down the strike by colluding with the state machinery and the RMMS, the officially recognized trade union, which had held a monopoly on speaking up for the workers. After this, about 91,251 mill workers were laid off.

The catastrophic outcome of the strike also had national-level implications, as Mumbai’s mill workers held the vanguard position of the country’s labor movement. The failure of the 1982–83 strike crucially led to the reversal of the entitlements that the mill workers had obtained through various struggles and fundamentally altered workers’ claims over the city’s social fabric. Following the strike, the workers lost the fighting spirit that they had demonstrated historically. Most importantly, the failure of the strike resulted in the gradual dismantling of the various social, political, and cultural institutions that contributed to the rhythms of Girangaon.

The failure of the strike was not merely a loss of that industrial action; it had ramifications for future strikes by the working classes. Since the late 1980s, protests by the working classes in Mumbai have become increasingly weaker in staking their claims. The disastrous outcome of the 1982–83 strike, thus, not only resulted in working classes losing their rights and privileges earned through various decades of struggles but it also heralded the unmaking of kaamgarachi or shramikanchi (laborers) in Mumbai.